Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission has called on all Canadians to begin their individual and collective journey toward “truth” and “reconciliation.” This journey, notwithstanding its challenges, is one that Canadians are beginning to walk. It is our hope that all Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians embrace the Truth and Reconciliation’s Calls to Action in their everyday lives. Is there a better place to begin the work of learning, sharing, changing, and transforming – individually and collectively, than in our classrooms? We think not.

The Truth and Reconciliation Curriculum Linked Guides have been created to speak and relate to the power of teaching and learning through one’s heart. This pedagogical approach is widely known as relational learning. This type of learning profiles opportunities for teachers and students not only to use their heads (cognition), but also, their hearts (affect). This kind of learning takes students, indeed all of us, into the heart of difficult knowledge about Canada’s settler colonial history of cultural genocide. As such, we encourage teachers to consult resources such as: Let’s Talk! Discussing Race, Racism and Other Difficult Topics with Students and the Handbook for Facilitating Difficult Conversations in the Classroom. Moreover, before using each guide make sure to send the letter that you can find on pages 12, 13 and 14.

The lesson plans in these guides draw on historical inquiry, critical thinking and affective pedagogies to teach students about the Indian Residential Schooling system, intergenerational trauma, and the strength and resilience of the Survivors, their families, and communities. Through each activity, students will become familiar with local Indigenous communities and the rich cultural traditions that Indigenous communities strive to preserve, despite years of settler colonial oppression. Students will also have opportunities to learn what reconciliation means and how they can embody reconciliation principles and relationships.

In the case studies, students may move beyond simply ‘studying’ reconciliation toward standing with Indigenous Peoples. There are many different perspectives on what “reconciliation” means for different Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. To recognize such differences, the curriculum guides do not attempt to speak on behalf of all of these differing perspectives, but rather they seek to open an introductory window to the many conversations that need to take place. In particular, throughout the course of these lessons, students will learn about reconciliACTION, a term first coined by the Cree Nation’s Stan Wesley (2016) to qualify how reconciliation must involve actions that lead to positive change for the well being of Indigenous Peoples.

The series of lesson plans in each guide are framed via a “case study” format. Each case study focuses on one of the following Indian Residential Schooling system within the province of Ontario: St. Anne’s in Grade 10, Cecilia Jeffrey in Grade 8, and the Mohawk Institute in Grade 6. Each case study utilizes the Project of Heart as its curricular and pedagogical framework for studying and enacting our commitment to the 94 Calls to Action put forth by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

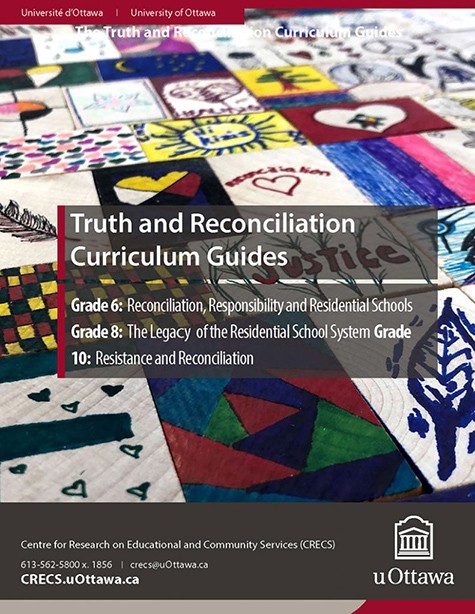

Project of Heart was highlighted by the Truth and Reconciliation in its Final Report (2015) because of its exemplary pedagogy that embraces students’ creativity and sense of justice to invoke their civic responsibility in response to the 94 Calls to Action. Actions that lead to positive change for the well being of Indigenous peoples are the kinds of responsibilities that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission challenges all Canadians to embrace. For those of you who are not familiar with the Project of Heart pedagogy, you can visit the national website at http://www.projectofheart.ca and check out what other communities of inquiry across the country are doing. You may also find other resources by checking out Project of Heart BC and SK.

Teachers can do Project of Heart as a collaborative inquiry project with students to create and facilitate an ethical space, which in turn encourages them to respect each other in all their differences. It also seeks to acknowledge and harness students’ strengths as they work through “difficult knowledge.” In these lesson plans, students are encouraged to exercise their strengths (using art and activism) to both empower and activate personal agency. This relational pedagogy also affords students opportunities to empathize with people they do not “know,” how reconciliation must involve actions that lead to positive change for the well being of Indigenous Peoples.

Teachers and students will have opportunities to participate in reconciliACTIONS via the existing campaigns of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society learning about “Shannen’s Dream,” “Jordan’s Principle,” and “I Am A Witness” campaigns. Through these campaigns, students will learn about ways to support those who still do not have access to services most Canadians take for granted, such as clean water to drink and “comfy” schools to learn in. Furthermore, students will learn how to counter the ignorance of racism in their own families and communities by expressing the “truths” they learn throughout the lessons, with the hope that they are able to counter the myths that endure within Settler communities.

We are deeply humbled and would like to recognize and thank the invaluable contributions of Residential School Survivors, Evelyn Korkmaz, Irene Barbeau, and Jenny Tenasco, who are part of the writing team. They worked diligently on these documents at great cost, as the subject matter moved them to relive the intergenerational trauma they suffered while attending residential school and continue to heal with their families today. The stories of Elders and Survivors who share their experiences of growing up attending Residential Schools and the intergenerational impact they experience are at the heart of the lessons. Despite the traumatic injustices they have faced, these women have generously shared their knowledge and hope for living relations of reconciliation as Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

Wherever possible, sharing circles have been used in the guides to foster the self-reflexive work that is a necessary part of the process of reconciliation and restorative justice. They can be a powerful pedagogical method for students to listen, share, heal, and reflect on what they have learned through the various activities in the guides.

Before facilitating a sharing circle, it is important, if possible, to establish relationships with community members of the traditional territory you are on to better understand their protocols, teachings and traditions. Inviting an Elder to your classroom can be very powerful opportunity to learn from their stories and traditional knowledge. Collaborating with Elders and/or knowledge keepers from local Indigenous communities can also help to ensure that their knowledge is honoured and respected both inside and outside of a sharing circle and your classroom. Not all Indigenous communities have the same protocols for sharing their knowledge, and it is important to respect and understand the social and cultural differences. It is not always possible to consult with an Elder or for an Elder to have the time to be a guest in your class. Consequently, when facilitating circles remember to frame your teaching and learning as a steward of your classroom community’s “truth” and “reconciliation” journey. To the best of your ability share with students how the traditions are not yours, and that you are trying to implement them from a place of honour and respect. Although protocols for facilitating sharing circles vary, there are some common features for certain communities:

- All members are treated equally and with respect in a safe setting;

- Teachers and students take turns to speak;

- Speak from the heart; and

- Listen with an open heart and mind that is free of judgment.

Teachers are encouraged to have conversations about the concepts of talking circles and restorative justice. Stereotypes, insensitivity, categorization, generalization and abstractions are complex and systemic issues that must be investigated with students prior to facilitating a talking circle. For more information on the pedagogical concept of talking circle, visit First Nations Pedagogy Online and Ministry of Education.

Through these guides, students will develop their critical and historical thinking skills, and demonstrate their learning with varying levels of grade-appropriate emphasis. The guides scaffold student learning utilizing the six historical thinking concepts, including establishing historical significance, analysing primary source evidence, understanding continuity and change, identifying causes and consequences, comparing historical perspectives, and understanding the ethical dimension of historical interpretations (Seixas & Morton, 2012).

These concepts allow students to practice historical thinking that goes beyond “knowing the facts”, as this is particularly important when dealing with the history of residential schools and the work of reconciliation. The guides call on students to investigate primary sources that detail Canada’s implications in residential schools, and allow students to understand how the past impacts the present. Students gain skills in critical thinking by looking at the connections between the causes of the Indian Residential School System and the ongoing consequences for Indigenous peoples. In the case studies, students learn not only about the significance of residentials schools on the lived experiences of Indigenous peoples, but also about how we can work toward reconciliation, by taking responsibility for the past and gaining insight through Indigenous ways of knowing. These critical and historical thinking skills are crucial to the Project of Heart’s aim of highlighting the ethical imperative to act against ongoing injustices in the true of spirit of reconciliation.

Grade 6 – Case Study 1 (Mohawk Institute):

In this unit on the Mohawk Institute, students are engaged with all six of the Historical Thinking Concepts as they learn about a Mohawk community (Kahnawake), and the significance of the revitalization of the Mohawk language. For instance, in lesson two, students learn about the history of residential schools and the Mohawk Institute. Through a timeline activity, reading and discussion questions, students are engaging with historical significance and ethical dimensions as they think about the significance of the Mohawk Institute and how it affected the Mohawk community. Next, students will be thinking about cause and consequence in lesson four when they hear an account from a residential school survivor. Here, they will learn about the direct impacts of the Mohawk Institute on the individual who attended. Engagement with the Historical Thinking Concepts is echoed throughout the unit as the lessons have students thinking deeply about Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples past and present, the effects of the Indian Residential School System and their own role in reconciliation efforts.

Grade 8 – Case study 2 (Cecilia Jeffrey Residential School):

In this unit, through group discussions, personal reflections and engaging activities, students are involved in thinking about all six of the Historical Thinking Concepts. For instance, in lesson three, students are engaging with multiple historical thinking concepts through a stations activity. By exploring a variety of sources, including primary source evidence, students are discussing, through question prompts, about the historical significance, historical perspective, cause and consequence, and ethical dimensions of the treatment of Indigenous individuals in the Cecilia Jeffrey Residential School. In lesson five, students are learning about resistance to government imposed legislation from Indigenous groups in the past and in the present, thus engaging with continuity and change. They are also engaging with historical significance as they think about the importance of the preservation of Canada’s Indigenous cultures and research Indigenous culture revitalization efforts.

Grade 10 – Case Study 3 (St. Anne's Residential School):

In this unit, we delve deeply into the Indian Residential School System, and, more specifically, St. Anne’s Residential School, so that students can engage with the question of reconciliation and refine their critical and historical thinking skills. Lesson one engages students in a station-based learning strategy that seeks to deepen their understandings of the each historical thinking skills, including examinations of evidence, historical significance, historical perspectives, cause and consequence, continuity and change, and the ethical dimension. As the unit progresses, students then practice these ways of thinking and analyzing. In lesson two of the unit, students engage with various government legislation and policies in order to cultivate a robust understanding of the historical significance of residential schools. In lesson four, they then create a detailed timeline of the causes and consequences of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), examining how issues such as the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, and children in care all affect – and are affected by – the TRC. Finally, this unit engages heavily with historical perspectives and the ethical dimension, as students are guided to grapple with their own role in reconciliation efforts across the country.

The teacher guides have been developed to address the Social Studies Grade 6, History, Grades 8, and 10 curricula. Students will be able to identify the short and long-term impact that the residential school system has had on Indigenous people of Ontario and across Canada as a whole through the close study of those affected in the particular community that is doing the Project of Heart. Using a range of modes, students will discuss how the residential school system took hold across Canada and show why it has had such devastating outcomes. Students will also demonstrate their knowledge of how the resilience of residential school survivors is contributing to cultural revival and the process of reconciliation.

Using a backward design model, the disciplinary based teacher guides students will identify the short and long-term impact that the residential school system has had on Indigenous people of Ontario and across Canada as a whole through the close study of those affected in the particular community that is doing the project of heart. Students will discuss through a range of modes how the residential school system evolved across Canada and show why it has had such devastating outcomes. Students will also demonstrate their knowledge of how the resilience of residential school survivors is contributing to cultural revival and reconciliation.

The teachers’ guidebooks for each grade level have been created using the seven key principles of Growing Success to ensure that assessment, evaluation, and reporting on the overall outcomes are valid and reliable. Following the backward design model, each guidebook identifies the key insights for students to know to develop their competencies in relation to the achievement chart, learning skills and work habits. Rich performance tasks, daily activities/assessments to prepare students along with assessment tasks and tools are provided. The inquiry-based rich performance tasks allow students to explore real issues and problems, present their findings to a wide range of audiences, allow for academic rigour through multiple paths of learning, include assessment for and as learning, incorporate teamwork and collaboration, and embrace the communication of student ideas, student design and adjustment of their own hypotheses.

This approach supports students’ learning and success through teaching practices and procedures that are fair, transparent, and equitable for all students. The guide underscores the need for a flexible learning environment that accommodates individual learning differences and accommodates multiple points of entry to allow for the interests, learning styles and preferences, needs, and experiences of all students. Moreover, because of the nature of the necessary journey each student must go on in their learning to identify with the issues and make a relation to the local and global significance of their knowledge, through the course of the learning experience, there are multiple opportunities for students to demonstrate the full range of their learning and for teachers to provide ongoing descriptive feedback. This competency-based resource also allows for students to assess their own learning and goals through the reflexive process that is required to meet overall expectations.

In line with the aims of Learning For All, this curriculum inextricably links assessment and instruction to engage students in learning and supporting student success. The teachers’ guides provide a comprehensive overview with step by step plans with instructional strategies for delivery that will support all learners by following the tenets of Universal Design for Learning and providing a range of suggestions for differentiated instruction.

It is important to note that although the teacher's guides have been created to specifically address the Social Studies curricula, there is a rich opportunity for these guides to be used in cross-curricular and integrated learning contexts, especially in the Grade 6 classroom. As noted in the Ontario English Language Curriculum, teachers can use these social studies reading materials in their language lessons and incorporate “how to read non-fiction” materials into their social studies lessons. Since all subjects require students to communicate what they have learned, using a cross-curricular approach will “help students develop their language skills, providing them with authentic purposes for reading, writing, listening, speaking, viewing, and representing” (p.23). Teachers may also want to use an integrated learning approach and link English Language expectations into the lessons and rich assessment tasks provided in these guides. By linking expectations from different subject areas, students are provided with multiple opportunities to reinforce and demonstrate their knowledge and skills.

Lead writers on this project are Nicholas Ng-A-Fook, Linda Radford, Sylvia Smith, Kiera Brant-Birioukov and Cindy Blackstock.

Nicholas Ng-A-Fook is a full professor at the University of Ottawa and the Director of Teacher Education. For almost two decades Dr. Ng-A-Fook has collaborated with different national and international Indigenous communities to develop culturally sustainable, relevant, responsive, and relational curriculum materials. He has documented such work in several publications. He has collaborated with the Kitigan Zibi education sector, Algonquin Elders, First Nations Kikinamadinan elementary teachers, and teacher candidates to develop several different educational resources that address different aspects of the Ontario Curriculum.

Linda Radford is a long-term appointment professor at the University of Ottawa and the Lead of its Faculty of Education Urban Communities Cohort. Dr. Radford works with teacher candidates who do their teaching placements at schools which have high populations of FNMI students. She has collaborated on archival work and the development of community-based materials with an Inuit Association, worked with teachers at Kitigan Zibi school, and has co-developed curriculum around Indigenous literature, recently focusing on creating resources for Understanding Contemporary First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Voices to Grade 11. Her recent publications focus on supporting teacher candidates learning to teach for reconciliation.

Sylvia Smith is a former teacher with the Ottawa Carleton District School Board and Governor General Award Winner for Teaching Excellence in History for creating Project of Heart. She is also the founder of Justice for Indigenous Women. Sylvia was inducted as an Honorary Witness to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015 for her work with Project of Heart.

Kiera Brant-Birioukov is Haudenosaunee from Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, ON. She is currently a PhD student in the Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy at the University of British Columbia, where her research is grounded in curriculum theory, teacher education, and ethical Indigenous education. She is a primary teacher in Vancouver and has worked as an Indigenous Advisor at the University of Ottawa.

Lorna McLean is a full professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Ottawa. She teaches Social Studies and Language in the Teacher Education Program and, in the Graduate Program, she teaches courses on historical narratives and commemoration. Her research interests include the history of education, citizenship and curriculum.

Andrea Auger is Ojibwe and a member of the Pays Plat First Nation. She joined the Caring Society in 2008 to work on the Touchstones of Hope and is also an editor of the First Peoples Child and Family Review. With a background in education, her areas of expertise include engagement in reconciliation, reconciliation approaches, child and youth engagement, and human rights.

Keri-Lynn Cheechoo is Cree and from Long Lake #58 First Nation. She is a part-time professor and PhD candidate at the University of Ottawa whose work takes up the existing missing histories of the state sponsored policies of forced sterilization of Indigenous women. She is currently also a Pre-Doctoral Fellow at Queens University and an adjunct professor there.

Jessica Gladu is a current Ontario College of Teacher member a MA in Education student at the University of Ottawa studying digital citizenship education in urban schools. As a graduate of the University of Ottawa’s B.Ed. program, she studied how to incorporate Indigenous perspectives in her teaching subjects History and English.

Jennifer Bergen is a part-time professor and PhD candidate at the University of Ottawa. Her work focuses on inquiry-based and anti-oppressive history and civic education.

Lisa Howell is a part-time professor and PhD candidate at the University of Ottawa whose work focuses on reconciliation pedagogy and decolonizing social justice in teacher education. She is a former elementary teacher at the Western Quebec School Board, where her work with Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth was recently recognized with a “Partner in Indigenous Education” award from Indspire and a Governor General’s History Award for excellence in teaching.

Trista Hollweck is a part-time professor and PhD candidate at the University of Ottawa whose work focuses on relational pedagogies and coaching and mentoring of teachers. She is also a part-time consultant at the Western Quebec School Board.

Jenny Tenasco is a survivor from Cecilia Jeff rey Residential School. She is a graduate from the Child and Youth Worker program at Algonquin College and is part of the Algonquin Anishinabeg First Nation, where she is both an Elder and works at the Kitigan Zibi School in Special Education. She is the mother of three children, two grandchildren and one great grandchild.

Anita Tenasco is a proud member of the Anishinabe / Algonquin Nation and a member of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg community. Anita is a mother, grandmother, daughter, sister and spouse who was born and raised in Kitigan Zibi, Quebec. Anita Tenasco is the Director of Education for the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg. She has a college diploma in Social Sciences, a Bachelor's Degree in History from the University of Ottawa, a Bachelor's in Education from the University Ottawa, as well as a First Nations leadership certificate from Saint Paul’s University, in Ottawa.

Evelyn Korkmaz is a Mushkegowuk Cree from Fort Albany First Nation, Ontario. She has lived in Ottawa for many years. Evelyn is a survivor of the notoriously violent St. Anne’s Residential School that was operated by the Catholic Church, in her community from 1903 to 1976. Evelyn aspires to break the long held silences of horrific abuses against Indigenous children who were removed from their families and forced to reside in federally mandated residential schools. Evelyn has expanded her role as a human rights activist; and is also co-founder of the global organization called “Ending Clergy Abuse” (https://www.ecaglobal.org/). Her goal is to give a voice to all those victims who have been silenced by child trauma, silenced by the abusers, and/or silenced by the church.

Irene Barbeau is a survivor who attended the Shingwauk Residential School. She is the founding president of The Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association. She is retired from the Federal Government after 25 years of service in the departments of Aboriginal Affairs, Health Canada, Veterans Affairs, and the National Museum of Canada. She was awarded the 150 Medal of Canada for volunteering and making her community a better place to live. She is the mother of two daughters and the grandmother of four.

The writing team would like to thank the rest our team of curriculum evaluators and teachers piloting this curriculum: Nancy Henry, Instructional Coach of Indigenous Education for the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board (OCDSB); Barbara Brockman, Glashan Public School OCDSB; Jeff Beckstead, Meadowlands School OCDSB; Heather M. Kirk, Vincent Massey Public School OCDSB; Kim Esselaar, Queen Mary St. Public School OCDSB; Rebecca Clarke, R. E. Wilson OCDSB; Marilyn McMillan, Hillcrest High School OCDSB; Deb Lawlor, Coordinator of Intermediate/Secondary Student Success at Ottawa Catholic School Board (OCSB), and Michael Bernards, Lester B. Pearson OCSB.